In 1919, Johnston McCulley began to write a series of popular novels about a swashbuckling champion of justice. Dressed in black, disguised by a mask over his eyes, this adventurer was a master horseman and an expert swordsman, who moved silently and swiftly by night. He left a unique calling card, a “Z” slashed into the clothing or, sometimes, the flesh of his adversaries. The identity of this masked man remained a mystery to his enemies; he was known only as Zorro, Spanish for fox.

The popularity of McCulley’s works carried over into cinema, with Douglas Fairbanks playing Zorro in a successful silent film and Tyrone Power reprising the role in a later sound version. Zorro then made the move to television with a series produced by Walt Disney Studios.

McCulley was inspired by tales of the exploits of bandits in California in the 1850s, when political and economic power was moving from the Californios to the ever- growing number of Anglos, many of whom attracted by the lure of gold. The story of one man in particular fascinated McCulley, that of Salomon Pico.

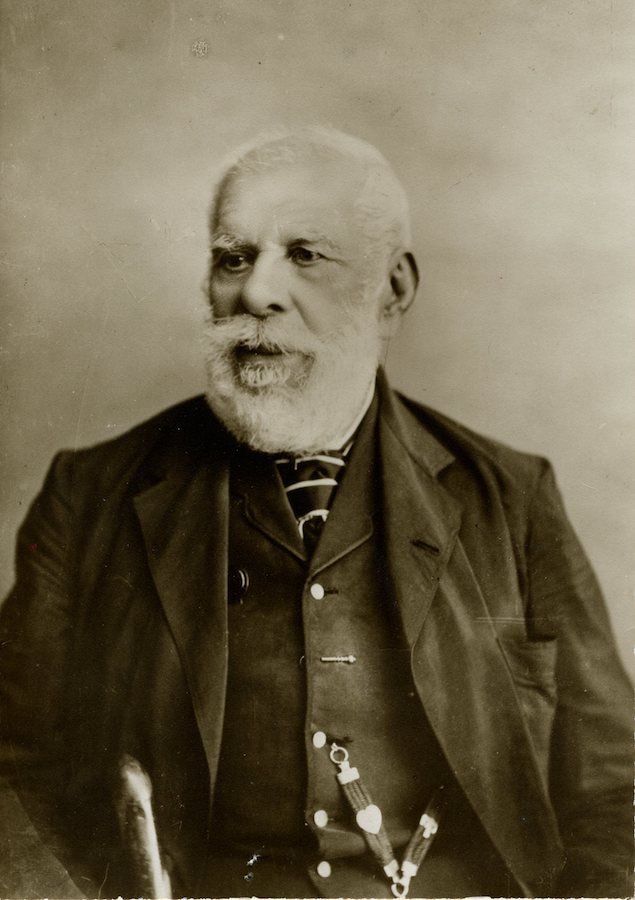

Salomon Pico was born near San Juan Bautista in 1821. His father was a career soldier who served in garrisons up and down Alta California including Santa Barbara. The family was one of the most distinguished in California; numbered among Salomon’s cousins were Pío Pico, the last Mexican governor of California.

Much of Pico’s life is enshrouded in myth. It is known he was the grantee of a rancho in today’s Tuolumme County in 1844. It has been speculated that loss of this property drove Pico to crime. In any case, by the late 1840s he was terrorizing Americans traveling on the roads of Southern California. One of his favorite bases of operation was the Drum Canyon area south of present Los Alamos. Here he would lie in wait, ambush, kill, and rob his victims, the bodies of whom were often never found. Perhaps the most famous story about Pico concerned his habit of cutting the ears off his victims and using them to make an especially grisly necklace.

In the mid-1850s, Pico became a semi-permanent resident of Baja California. Here he boasted to one Alfred Green that he had killed 39 Yankees during his Alta California days. Soon he was on the run from authorities in Baja as well. In 1856 he stabbed an Englishman to death in a La Paz restaurant in the mistaken notion that he was a Yankee. Pico’s life came to an end in May 1860, when he and several other suspected outlaws were executed by firing squad.

The story of Salomon Pico soon passed into folklore — a man taking vengeance on those who had wronged him, a guerrilla warrior fighting to save his homeland from an unscrupulous invader. It’s likely Pico was protected from capture to a certain extent due to the growing tensions between the Californios and American authorities. McCulley melded Pico’s story and additional outlaw tales to create the character of Zorro. In deference to his 20th-century American readers, he placed Zorro in Spanish California, battling corrupt Spanish authorities, rather than American. McCulley’s stories of a highly romanticized and pastoral Spanish California actually have their roots in a troubled transitional era of California history.

This article originally appeared in the Santa Barbara Independent.